The South African novelist and anti-apartheid activist Nadine Gordimer (1923-2014) published a short story collection in 2007 entitled Beethoven Was One-Sixteenth Black. The title story is about a multiracial university professor in Johannesburg, thinking back over his life and his identity:

Beethoven was one-sixteenth black

Once there were blacks wanting to be white.

Now there are whites wanting to be black.

Is the Blackness of Beethoven a thing?

In 1934, the Jamaican-born journalist Joel Augustus Rogers (1880-1966) published a book called 100 Amazing Facts About the Negro with Complete Proof (a title borrowed by Henry Louis Gates, Jr. for a recent book of his own). As Gates notes about the author of the first 100 Amazing Facts:

Speculations that Beethoven was of “Moorish” (i.e. African) ancestry date back to the composer’s own lifetime. Nineteenth-century biographers have described his dark complexion, “flat, thick nose,” and “thick, bristly [and] coal-black” hair. J.A. Rogers and others later suggested that Beethoven’s mother had transmitted African ancestry to her son by way of her Flemish forebears; the Low Countries had been under Spanish rule in the sixteenth century, and Spain had been ruled by Muslims (or Moors), originally from North Africa, off and on from the eighth to the fifteenth centuries.

If Beethoven did in fact have even this very small claim to African ancestry through his Flemish mother, it would have been enough to make him subject to the laws of segregation in the Jim Crow South..

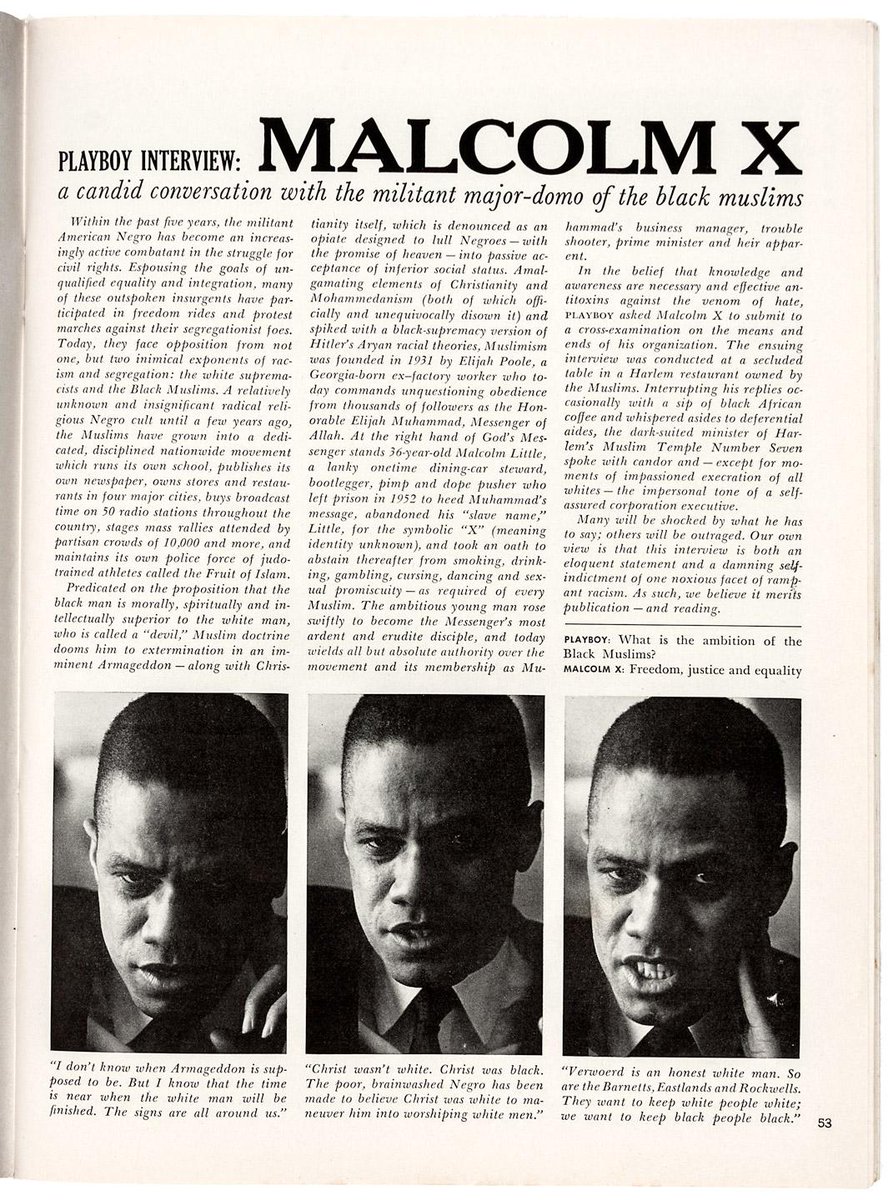

The belief that Beethoven was Black became popular in the 1960s and 1970s during the Black Power movement. Stokely Carmichael mentioned it in his speeches to students, as did Malcolm X in a famous interview he gave to Alex Haley in Playboy in 1963.

Although claims of Beethoven’s Black ancestry has been refuted by scholars, the idea has never stopped cropping up in unexpected places.

It appears, for instance, in this excellent recent picture-book biography of Arturo Schomburg.

A project called “Beethoven Was African” aims to show that the polyrhythms Beethoven used in his piano sonatas bear a resemblance to the polyrhythms of West African drumming. Listen here:

Reviewing the Beethoven Was African project, the music critic Tom Service writes:

My initial response to the question, “Are Beethoven’s African origins revealed by his music?” that has been asked at the website Africa Is a Country, is a definitive “no.” It is based on questionable premises that lack real historical evidence, at least to the story of Beethoven and his music over the past couple hundred of years.

This is far from a new idea. Here, Nicholas T Rinehart outlines the century-long history of the “Black Beethoven” trope and analyses the cultural and racial politics that have made this such a potent idea. He suggests our attraction to the notion that Beethoven was black is a symptom of classical music’s tortured position on race and music: “This need to paint Beethoven black against all historical likelihood is, I think, a profound signal that the time has finally come to make a single … and robust effort [to reshape] the classical canon.”

In the past few months, classical music institutions have begun to recognize their need to reconceive the widespread impression of classical music as a strictly white and European art form. The #TakeTwoKnees hashtag in the wake of the murder of George Floyd was an effort by Black classical musicians to address this.

The Beethoven-was-black trope raises other questions as well:

- Arguments for Beethoven’s “Blackness” are based on hearsay, speculation, and the reading of visual images. Are these reliable sources of evidence? If not, what sources of information would be more reliable?

- Is race something essential? Is it something defined by visible markers? Or is it something defined by affinity, that is, by what one loves, desires, or wishes to be?

- Who gets to decide the racial identity of another?

- Does the fact that Beethoven’s music expresses an ethos of struggle, and of triumph over struggle, make it Black?

Which leads to even thornier philosophical questions:

- What is Blackness? What is race?

The piece often used as a marker of Beethoven’s blackness is his last piano sonata, op. 111 in C minor. The second movement is in theme-and-variations form, and the variations become more abstract as the piece continues. Two of the variations are highly syncopated, which has led some to retrospectively credit Beethoven, in this sonata, with “inventing” ragtime, and even jazz.

Babatunde Olatunji demonstrates west African polyrhythms.

Daniel Barenboim demonstrates Beethovenian polyrhythms.

Incidentally, Beethoven had a Black friend and colleague, George Polgreen Bridgetower, who was a famous Afro-European violinist and for whom Beethoven wrote a fiendishly difficult violin sonata. The original dedication to his friend reads, with fond humor:

Sonata mulattica composta per il mulatto Brischdauer [Bridgetower], gran pazzo e compositore mulattico

(Mulatto Sonata composed for the mulatto Brischdauer, great madman and mulatto composer)

However, the two fell out while drinking together one evening, after Bridgetower suggested that the woman Beethoven was in love with had loose morals. As was his habit when his friends and idols displeased him, Beethoven scratched out the dedication to Bridgetower on the Violin Sonata no. 9 in A Major and replaced it with a dedication to another violinist, Rodolphe Kreutzer, after which it became commonly known as the “Kreutzer Sonata.”

Leave a comment